What we eat and how we produce food matters. Food systems are responsible for more than a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions.

We cannot fully tackle the climate crisis without reducing the greenhouse footprint of our food. The issue is only becoming more and more urgent as the world's population grows alongside hunger resulting from the disruption of food exports by war. As people become wealthier and more urbanized, the global consumption of meat and dairy products is also increasing.

Livestock is the main source of our food emissions and the world's third largest source of emissions with 14.5%, after energy (35%) and transport (23%).

To reduce these emissions, many advocate switching to plant-rich or plant-only diets. But will people with a long-standing attachment to meat actually choose to change? Our new research suggests the sweet spot is the Mediterranean diet, which includes meat while remaining plant-rich and healthy.

What is the problem?

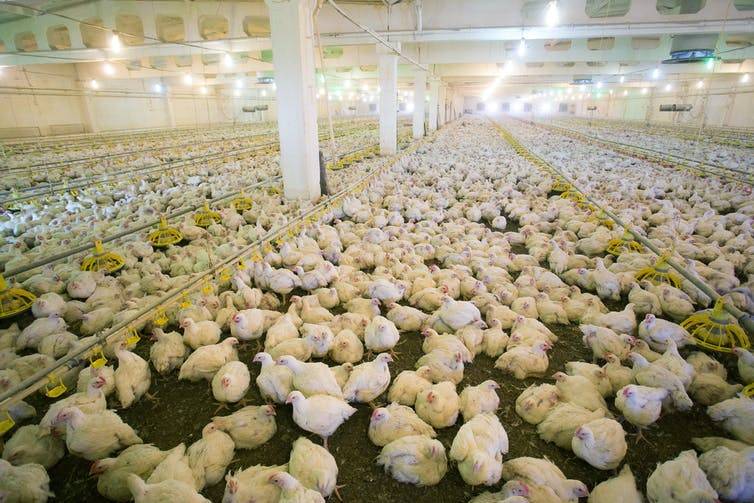

Raising livestock requires large areas of land, as well as water and feed inputs. More intensive livestock production is linked to loss of biodiversity, land degradation, pollution of waterways, increased risk of zoonoses such as COVID-19, and antibiotic resistance .

Intensive animal husbandry often leads to a deterioration in animal welfare. Shutterstock

While methods of reducing livestock emissions are under development , production is only half the story. To have a real impact, we must also consider demand.

Without reducing overall demand for meat and dairy, livestock emissions are unlikely to decline fast enough or far enough. In wealthy countries like Australia, we consume meat and dairy products at high rates. Reducing these consumption rates could reduce greenhouse gas emissions and reduce other environmental damage.

So what diet should we eat? Obviously, any acceptable diet must be nutritionally adequate. Although meat provides essential nutrients, too much of it is linked to diseases like cancer . It is important to consider the environmental and health credentials of a diet. We can also add animal welfare to this, which tends to be worse in intensive animal production .

We hope that by identifying healthy and environmentally friendly diets with improved animal welfare, we can help people make sustainable food choices.

What did we find?

We looked at five common plant-rich diets and assessed their impacts on the environment (carbon footprint, land and water use), human health, and animal welfare. We focused on food production in high-income countries.

The diets we looked at were:

- Mediterranean (plant-rich with small amounts of red meat, moderate amounts of poultry and fish)

- Flexitarian/semi-vegetarian (meat reduction)

- Pescatarian (fish, no other meat)

- Vegetarian (no meat but dairy and eggs OK)

- Vegan (no animal products)

These five plant-rich diets had less impact on the environment than the omnivorous diet, with meatless diets (vegans and vegetarians) having the least impact.

We must, however, add the caveat that the environmental footprint measures used to compare diets are simplistic and overlook important indirect effects of dietary change.

Overall, the Mediterranean diet was considered the healthiest for humans, while vegan and vegetarian diets had the best results for animal welfare. When we combined the three measures, vegan and vegetarian diets were found to be the most "sustainable" diets based on reducing our food footprint, maintaining health, and reducing negative impacts on farm animals. .

Vegetarian diets are better for the planet but less popular. Shutterstock

We know which diets are the best. But which diet will people actually choose?

There is often a gap between what we should be doing in an ideal world and what we are actually doing. To address this, we looked at what people are actually willing to eat. Is promoting a vegan or vegetarian diet the most effective way to reduce the demand for meat and dairy products?

To find out, we asked 253 Australians what they currently eat and which of five plant-rich diets they were willing to eat.

Australia is a meat-intensive country, so it's no surprise that most of our respondents (71%) identified themselves as omnivores.

It's also not surprising that the diets least likely to be adopted were vegan and vegetarian diets, as these diets represented a major shift in most people's eating habits.

As a result, the Mediterranean diet – which results in a slight reduction in meat consumption – was most likely to be adopted. Combined with its high health benefits and moderate impacts on the environment and animal welfare, we have identified it as the best diet to promote.

Although some of these results may seem intuitive, we believe that by combining social, environmental, human health and animal welfare elements of food consumption, we get a more complete picture to spot pitfalls as well as solutions. realistic.

For example, it's probably a waste of valuable time and resources to promote diets like the vegan diet that realistically most people aren't ready to eat. Yet despite people's obvious lack of enthusiasm, most research assessing the environmental impact of different diets has favored vegan and vegetarian diets.

This is why it is important to have a broader vision. If we are serious about reducing meat and dairy consumption, we need to use approaches that have the best chance of working.

In high-income countries like Australia, this means we should promote the Mediterranean diet as the best diet to start meeting the demand for emission-intensive meat and dairy. We need to start at a realistic point to start creating a more sustainable global food system.

Authors

Nicole Allenden

Nicole Allenden

PhD Candidate, School of Psychology, University of New England

Amy Lykins

Amy Lykins

Associate Professor in Clinical Psychology, University of New England

Annette Cowie

Annette Cowie

Annette Cowie is a Senior Principal Research Scientist in the Climate Branch at the NSW Department of Primary Industries, and Adjunct Professor in the School of Environmental and Rural Science at the University of New England. She receives research funding from NSW and Commonwealth government programs and rural research and development corporations. She is a member of Soil Science Australia and an adviser to the Australia New Zealand Biochar Industry Group and the Land Degradation Neutrality Fund.

Sources : The Conservation.

Posted on 2022-07-19 09:54

Comments