As anyone working seriously with Sustainable Finance for a few years, I have been following closely the discussions on sustainability reporting, especially with a focus in climate since late 2016 (when the TCFD was created), and, more recently, including also biodiversity issues, with work in progress for the creation of a Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), an initiative that I am involved with from the early inception in 2019.

The Task Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) makes recommendations for companies to publish information to investors on their governance and actions to reduce their climate change risks.

One of the early findings of whoever works in this field is that corporation disclosure is only one of the relevant sources of information to rely on. Public databases (including provided by public bodies) and information provided by media and relevant stakeholders must be combined with corporations reports in order to get a clear picture of their ESG performance.

The biggest challenge faced by investors and banks, as users of these information, is the lack of standardization, leading to the fact that corporations not always report on the necessary KPIs, but rather choose indicators that benefit them, omitting the ones that indicate a poor ESG performance – as long as they are free to do so.

Indeed, in most countries of the world, there is no mandatory ESG reporting yet, and, where there is, the minimal contents is usually too vague to promote standardization.

There is a trend in developed markets to make TCFD recommendations mandatory (as done in the UK recently, but only from 2025 on), but, although TCFD provides a useful framework, especially compared to what previously (did not) existed in terms of climate risks, it’s not clear yet if all the key information needed by investors are really included in it. For example, TCFD defines climate physical and transition risks, being the first ones directly linked to the risk of natural disasters (deriving from climate change) and to the sea-level rise (which is reducing the area of seacoast real estate). However, TCFD recommendations do not require that companies disclose the location of their operations or other real estate assets, which is more than essential to an assessment of physical risks.

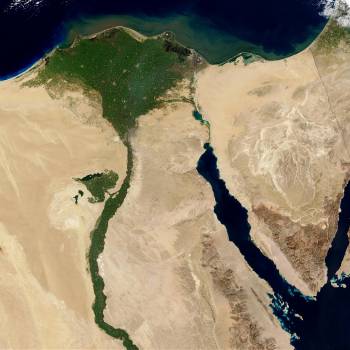

Regarding biodiversity risks, which comprises risks to fauna, flora, soil, freshwater, oceans and air, information on location is also essential, once the impacts of the same economic activity varies across different biomes/ecosystems, not only because of their different characteristics, but also because of their different levels of saturation of their boundaries (considering the previous human activities in the location). Also, the characteristics of local communities are also fundamental to understand the intensity of the risks and impacts.

However, capital markets regulators, whose mandates encompass the protection of investors interests and ensure markets transparency, still do not require the disclosure of this basic information: the location of companies’ operations and assets.

Furthermore, it’s widely known that, for certain industries, environmental or social risks or impacts derive mainly from the supply-chain (or from the customers). The classic example is the food industry, where the main impacts come from farmers, that might be involved, for example, with illegal deforestation, with modern slavery, or in conflicts with indigenous tribes.

Therefore, the consideration of climate physical risks, the relevance of natural carbon sinks (forests, mangroves, oceans) on climate change mitigation, as well as of other risks to flora, fauna, soil and watercourses, and the risks to local communities posed by economic activities that have a direct impact on nature (such as agriculture, mining, etc), it is easy to understand that supply-chain risk management is essential in terms of climate risks, biodiversity risks and social risks. So, corporations should disclose who are their suppliers, or at least their respective locations, as well as which are the measures they are taking to address the environmental and social risks arising from their supply-chains, disclosing quantitative key indicators over time. For traders, who provide inputs and finance to farmers, there is a similar need with respect to their customers.

Without transparency on these two key elements - location of operations and value-chain, investors and banks will never be able to make sound assessments of the ESG risk level of any corporation. TNFD scope definition is already recognizing the need to address the whole value-chain, but the need of locations disclosure remains to be addressed. Given the need to define industry-specific guidelines (as done by TCFD), as well as addressing the six dimensions of biodiversity (identifying appropriate metrics to do so), this work is supposed to last at least two years from its official launch later in 2021. It’s undeniable that the task here is much more complex than what TCFD did, once the latter needed to address only two aspects: GHG emissions and the protection of natural carbon sinks (and this one was focussed only generically).

Actually, capital markets regulators don’t need to wait for that in order to start to require the disclosure of these two key dimensions. Some pioneer investors are already requiring them to do so, as made by US asset manager Impax Asset Management, which requested in June 2020 to the US Securities Exchange Commission that it mandates corporations to disclose their locations. Also, investors can also engage collectively and require this information from investees, and rating agencies might downgrade companies who do not disclose the location of their operations and suppliers in their ESG ratings.

Of course, a regulatory approach would speed the process and this is certainly an information that corporations have readily available – no additional burden required, no space for excuses. And for regulators, all it takes is the due exercise of their mandates, once they are not the users of the information disclosed – the users are investors, banks and other stakeholders, such as business partners and civil society organizations. So, again, no additional workload, no reasonable reasons for any further delay. The IOSCO Sustainable Finance Network, created in October 2018, did not produce any substantial recommendations to its members yet – maybe this could be an excellent start.

IOSCO: International Organization of Securities Commissions The objectives of the International Organization of Securities Commissions are mainly the protection of investors, the guarantee of fair, efficient and transparent markets, the prevention of systemic risks, international cooperation and the establishment of uniform standards for the authorisation of stock exchanges and securities.

The revision of the European Non-Financial Reporting Directive, expected for this year, is another excellent opportunity to include this key information as minimum requirements of disclosure. By the way, it’s more than time to replace the term “non-financial” per something more precise, such as “Environmental, Social and Governance” or “Sustainability”, given the increasing body of evidences that ESG positive performance drives better financial performance, as evinced by this New Meta-Analysis From NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business and Rockefeller Asset Management Finds ESG Drives Better Financial Performance.

Let’s listen to science and move on from nice statements to relevant action – otherwise it will be too late.

Author

Sustainable Finance and Consensus Building Expert

Posted on 2022-01-17 07:00

Comments